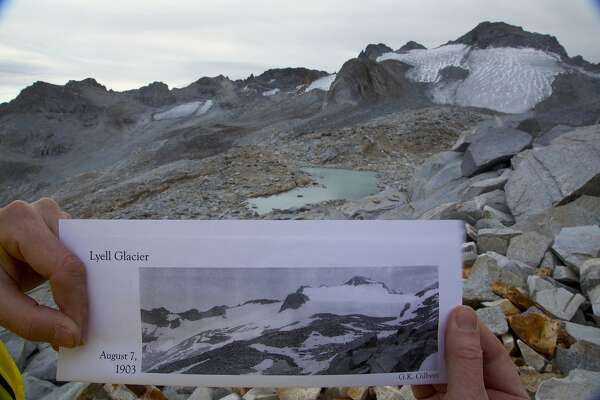

"For the past 148 years, Yosemite’s Lyell Glacier has taught us about the

Earth — how it was created, where it was going, and now, how it

might end"

What Remains

On a cool September morning in 2014, among lodgepole pines

under blue mountain sky, Greg Stock shouldered a backpack full of

camping gear and scientific equipment. Boyishly slender and athletic at

45, Stock is a climber, caver, and serious reader of books about

mountaineering and the natural world. He holds the enviable job title of

Yosemite National Park Geologist and mostly loves the work, especially

the part he was bound for that day — the study of Yosemite’s last two

glaciers.

Stock and several companions started their walk in

Tuolumne Meadows, the high-country jewel of Yosemite and everything that

I would ever wish to find in the pastures of heaven — many square miles

of grass and wildflowers surrounded by white granite domes that reflect

sunshine like polished glass. Stock followed the John Muir Trail south

out of those meadows into an immense U-shaped gorge called Lyell Canyon,

8 miles long and 3,000 feet deep, carved out of granite by

long-vanished glaciers during dozens of ice ages. Evergreens dot the

sloped walls of Lyell Canyon — straight lodgepoles down low, bent

whitebarks up high.

In that drought year of 2014, dry meadow

grasses carpeted the canyon floor in pale gold. Down the middle, the

Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne River trickled through wide, meandering

oxbows. The great irrigator of Tuolumne Meadows and drinking-water

source for San Francisco, that river thunders deep in spring but flows

in autumn thanks to meltwater from Stock’s destination, the

Lyell Glacier.

LEARN MORE